A tip from a wise friend, Thomas Steele-Maley, brought me back to some old school reading the other day: Theodore Sizer’s The Age of the Academies, from 1964. A look at the roots and fruits of the pre-Civil War “academy movement” in the United States, the little volume begins with a long essay by Sizer in which he describes the academies, their successes, and their ultimate failure and demise. His theme is that these quasi-private, generally exurban, comprehensive, largely boarding, and highly idealistic and idiosyncratic schools deserve a larger place in educational historiography. Where once I read this book as just an opportunity to fill in some gaps in my knowledge, I now find myself reading with a more focused, or maybe just older, eye. I was struck by a couple of curricular aspects of these schools, in particular the presence of surveying and navigation as fields of study.

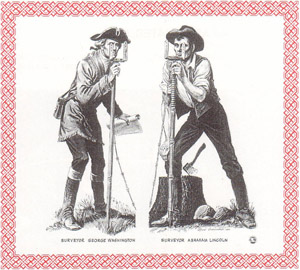

When I made much of my living teaching United States history I often found myself struck by the role of surveyors in our past; I even read a few books about them. Famously, George Washington started his career in this profession, and two British surveyors named Mason and Dixon left a lasting legacy with their eponymous opus magnum. As a kid growing up in the Holland Purchase and not far from both Holland, New York, and the intersections where the Two Rod and Four Rod Roads meet Big Tree Road in Erie County, New York, I was aware that all that we call home in this country was at some point measured and parceled out by surveyors and their land-speculating counterparts.

I also grew up with a fascination for the sea, and it had been impressed on me that the former student at my father’s school named Nathaniel Bowditch was named for the ancestor who had authored in 1802 The American Practical Navigator, a compendium of knowledge and advice that no doubt saved any number of mariners from leaving their bones on the ocean floor.

Navigation, like surveying, is a branch of applied mathematics, and, like surveying, it was an essential skill not only in measuring and mapping and getting from place to place but also in establishing the infrastructure for the American economy. Maritime commerce, like land speculation and sales, was essential to creating the wealth that allowed the young Republic to survive and thrive. And, like surveying, navigation was frequently a part of the curriculum of many of the little secondary schools that grew up in the American hinterlands as academies in the first half of the nineteenth century.

wealth that allowed the young Republic to survive and thrive. And, like surveying, navigation was frequently a part of the curriculum of many of the little secondary schools that grew up in the American hinterlands as academies in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Sizer notes in the opening essay of The Age of the Academies that even in that era there was a kind of schizophrenic attitude toward education, particularly the parts of it that concerned “practical” or life skills versus what we would today call the liberal arts—the study of history, language, and literature. Academy founders and supporters seem to have made their peace with a kind of dual curriculum, one that included things like surveying and navigation (and often bookkeeping) to fit young scholars for practical work and the other more bookish, to raise the level of discourse and discernment among the nation’s future active citizens.

Of course we have the same push-pull today, in almost identical terms and strangely similar forms. The epicenter of the discussion in our time lies around yet another branch of applied mathematics, computer programming. Coding, Edudemic tells us, is “the job of the future,” and hordes of educators, employers, and parents seem to concur. However well our laddies and lassies may be able to analyze The Great Gatsby, greet their Quebecois neighbors in French, or understand the causes of the Civil War, they must also be able to bend the power of the CPU to their will by cannily issuing a few commands in one or another of the technical languages known as “code.” (In a forthcoming article in Independent School magazine I explore the rise, or re-rise, of coding—which many of us learned in rudimentary form decades ago—and some of the motivations and methods behind the increasingly urgent movement to teach coding in our schools.)

As one who is interested in the coding phenomenon and something of a supporter, despite my misgivings about the pre-vocational nature of some of the pro-coding rhetoric, I find myself taking comfort in Sizer’s little essay and its reminder that there is a recurring theme—an applied-mathematical recurring theme, no less—in American education just as there is a recurring, or more likely constant, dichotomy in our thinking about what secondary schools should teach and, in a more broad sense, what they should do. Coding is simply the new surveying, just as I suppose was the “New Math” as it purported to help us catch up with the Soviet Union in the Space Race/Missile Gap era or was basic electrical theory in the Age of Edison and Marconi and Tesla.

new surveying, just as I suppose was the “New Math” as it purported to help us catch up with the Soviet Union in the Space Race/Missile Gap era or was basic electrical theory in the Age of Edison and Marconi and Tesla.

Poor mathematics (and physics)! Destined always to be the Most Important Thing in one form or another, and equally destined to be the thing that so many children and adults find hardest to master. But I shall leave the Why of that to better or more mathematical minds than mine.

I think seeing coding as the new surveying is actually helpful in putting all the hype in perspective. I would also point out that the primary practitioners of surveying and navigation and coding were usually the employees of the folks who earned the real fortunes, though there are certainly those who managed to master both the technical and business sides of the enterprise. (Walk around any New England seaport town and take a gander at the lovely homes built by some whaling and merchant captains; they might not be quite up to the standards of Bill Gates’s place, but for most of us they remain more aspirational than affordable.)

Until something comes along to change the American nature, I suspect there will always be the push-pull between the practical and the, er, what, the beautiful? the spiritual? the impractical? in American education. But at least we’ve been grappling with this problem for a couple of centuries, now, so the fact of the apparent conflict seems less alarming. The only alarming thing to me at the moment is the voice of economic anxiety and the presence of potential tools that could more or less erase the non-“practical” from the curriculum entirely. I think this would bring about the dystopia posited by Fritz Lang in Metropolis, and I don’t want it.

I like the push-pull we have and that we’ve had just fine, thank you, and I like thinking that it’s a matter of history and not some contrived “innovation.” I also like knowing that I am walking a path once trod by Theodore Sizer on his way to the Horace books, the Coalition of Essential Schools, and another “little” book I love dearly, The Students Are Watching. There’s still more to be learned from The Age of the Academies, and I’m happy to give some more time to learning it.